-

Posts

653 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Books

Posts posted by Hux

-

-

Just realised I posted on the 2021 thread, so here's a new one.

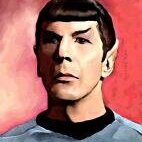

Star Trek: Strange New Worlds.

I gave up on Discovery after season two. Just awful. I stuck with Picard because I like so many of those characters (but it was even worse).

So far, Strange New Worlds has been... not too bad. They're exploring space, visiting aliens, and dealing with ethical dilemmas at least

-

Reading Death on Credit by Celine (sometimes translated as Death on the Installment Plan).

-

Shyness and Dignity (1999) Dag Solstad

A short novella about a man having a breakdown/epiphany/ awakening/you decide. Elias Rukla is a school teacher who teaches bored ungrateful 18-year-olds about Ibsen. After school one day (where he has once again failed to reach the pupils on any level) he becomes frustrated and destroys his umbrella in front of a crowd of bemused school kids. As he walks away, hands cut by the umbrellas ribs, he begins reminiscing about his life, specifically his student days and meeting his best friend Johan then later Johan's beautiful wife, Eva. After a few years Johan simply leaves his wife and young daughter behind to pursue a life in New York, abandoning everything (including his best friend Elias). Eventually, Elias and Eva begin seeing each other and build a life together, Elias taking on the responsibilities of being a husband and stepfather, all despite Eva not being in love with him.

I enjoyed this for the most part. I liked the themes it played with concerning frustrated ambitions, cultural malaise, the lack of a stimulating interlocutor, as well as the numbing ointment of possessing conventional (and socially approved of) successes (such as a beautiful wife). Elias spends a great deal of time talking about Eva's beauty and even more so about how it has faded as she approaches 50. In many ways, the disappeared Johan becomes a kind of symbol for those who have chosen to live the life they truly want (regardless of how many people it might hurt), while Elias embodies the unfulfilled life you quietly accept (shyly, with dignity). Until, of course, he experiences the classic mid-life crisis.

The book has no chapters and just meanders along as a wall of text to the end (which I don't care for) but this isn't entirely without justification. There is a stream-of-consciousness element to the book after all (less so the writing style itself), and a defeated man thinking about his life decisions over a short period of time. For the most part, I enjoyed the reading experience. He also references 'The Unbearable Lightness of Being' which this book reminded me of, sharing similar ideas as well as presentation style (though obviously not as good).

Overall, a very good piece.7/10

-

18 hours ago, lunababymoonchild said:

Reading or bought?Reading (after having been bought).

-

Shyness and Dignity - Dag Solstad.

-

The 🧡 is there but when I press it, a box comes up saying: ❕ Sorry, there was a problem reacting to this content.

-

No, I'm not seeing it either.

But I'm ready 🧡

-

Agostino (1945) Alberto Moravia

Short, coming-of-age novella about a boy called Agostino who, at the age of thirteen, begins to see that the world is slightly different from what it had previously been. He and his wealthy windowed mother are holidaying by the beach and taking boat rides together when a young man introduces himself into his mother's life. From here, Agostino begins to have an awakening which is further encouraged after he encounters a group of working-class boys (this also seems to be one of the themes of the book) who spend their time fighting, making fun of each other, stealing, and hanging around with a very suspicious man in his fifties (it is strongly implied that he is regularly engaged in consensual sexual activity with one of the boys which the others find amusing).

In the meantime, Agostini is beginning to notice (with the help of his new friends) that his mother is not just his mother but she is also a woman, with all the curves, mysteries, and attractions that all women possess. Where before her presence projected safety and warmth, she is now a symbol of his nascent fascination with the female form; this both attracts and repulses him. Until he finds a means of replacing her with an alternative in the discovery of a brothel where he wrongly believes his burgeoning interest in sexual matters will manifest a solution.

As someone who experienced the sudden arrival of sexual intrigue as a boy, this all felt very familiar to me. It's slightly disconcerting how the experiences of young boys in the '20s can be so similar to those a good century later. As a boy, me and my friend met a curious older man who was interested in young boys (nothing happened). As a boy, I also began to see my mother (specifically her relations with men) in a new light, one which altered my view of her as being merely a mother. I think Moravia quite brilliantly captures that awful moment when you're a boy of 12 or 13 when the world of sex and sexuality redefines everything in your life... forever.

The book is shorter than I realised and very easy to read. Excellent.8/10

-

The Journal of a Disappointed Man (1919) W. N. P. Barbellion

For most people, middle-age is the period in life when they first begin to feel the presence of their fragile mortality. As such, there is something unique, something terrible in fact, about a person in their twenties experiencing that same crisis due to a debilitating illness. Barbellion's journal begins when he is 13 and contains, as you might predict, a series of careless references to trivial matters which require diary entries of brevity and pure description. He is a boy fascinated by the natural world, by insects and animals, by the rapid arrival of knowledge and wonder. It's only in his late teens when the diary becomes something else, when Barbellion begins to notice that his body is showing strange signs of numbness and weakness. He knows something is wrong but doesn't know what, and only towards his last few years does he finally get a name for his illness: multiple sclerosis.

I generally don't read non-fiction books these days (and certainly not life writings) but this book (by title alone) had something that appealed to me. At this point I will reference the wonderful 'Book of Disquiet' by Pessoa, another diary but one which is more overtly creative and literary in its intentions. While that book has no chronology and feels like the random (and very beautiful) exploration of a man's private thoughts, this book (though also with a literary flourish to the prose) is a more coherent insight into the slow deterioration of a man's body and soul. As the journal goes on, the entries become longer and more reflective; as the illness progresses, Barbellion ceases to simply detail his day-to-day existence and instead begins to contemplate existence, to disclose more and more of himself, his inner turmoil, his fears and regrets, but more so (and very honestly), his (self-confessed) egotistical belief that he could have contributed something more had he lived longer.

There are some wonderful insights throughout the journal, entries which are exquisite, sad, angry and poignant. Towards the end, he endeavours to get the journal published and even succeeds, living long enough to hold a copy of the book (with an introduction by H.G Wells) in his hand. His original journal (the one he saw published) ended in 1917 and closed with the (false) words 'Barbellion died on December 31.' In realty he lived another two years and those last diary entries are also included here. The fact that he ended the original journal with a lie was based on the genuine belief that he would not live to see it published (or further material added). None the less, I interpret this as evidence that a certain creative license was indeed being enjoyed by Barbellion. That isn't to say the journal isn't a true account, but merely that he, like Pessoa, had a flair for the poetic and romantic.

The book was so easy to read, so wonderfully written. It offers so many amazing thoughts and phrases, the prose being truly magnificent, the subject matter, significant and powerful. I especially enjoyed the moment when he is talking to his wife about his impending death.

"[she] says widows' weeds have been so vulgarised by the war widows that she won't go into deep mourning. 'But you'll wear just one weed or two for me?' I plead, and then we laugh. She has promised me that should a suitable chance arise, she will marry again. Personally, I wish I could place my hand on the young fellow at once, so as to put him through his paces -- show him where the water main runs and where the gas meter is, and so on."

The man and his work deserves far more recognition. Superb10/10

-

10 hours ago, Hayley said:

I wonder, from your description, whether Sebastian Dangerfield is intended to be a bit of a caricature? It seems to play on a lot of exaggerated stereotypes of Irish men, anyway (ginger hair, drinks too much, charming and chatty yet deceitful). Did that come across as the intention in the book?

Possibly. It's worth noting that the Donleavy (like Sebastian) was an American who only arrived in Ireland after the war. He ramps up the Oirishness.

-

The Ginger Man (1955) J. P. Donleavy

The tale of a charismatic Irish-American (with an English accent) ne'er-do-well named Sebastian Dangerfield who spends his days crawling around Dublin. He is an alcoholic womaniser doing his best to avoid his wife, any kind of work, and his landlord. He's married to Marion with a young daughter but she leaves him (only to have him charm his back before she leaves him a second time). Sebastian has a number of other women on the go too, namely Christine who he makes grandiose promises to, and a young girl he seduces at a party (also receiving the same promises), then finally his wife's very own lodger, Mary, an older religious woman with a vigorous appetite for sex (she firmly believes putting it up the bum is less of a sin). Sebastian has a series of equally disreputable friends including O'Keefe, who, failing to get laid, leaves for France and decides to have sex with young boys instead (openly detailing this in letters to Sebastian). The plot follows Sebastian as he flounders from one situation to the next, one drink to the next, one pound note to the next.

I really enjoyed this book and, despite how unpleasant he could be (casual violence towards his wife and Mary), it was difficult not to be (like everyone else that encounters him) charmed by Sebastian Dangerfield. He has the gift of the gab and always appears to land, relatively speaking, on his feet. A charming rogue with a twinkle in his eye who lives very much in the now.

That all being said, the writing style was often frustrating. It switches from third person to first person on practically every page. But worse, it also jumps into Sebastian's head giving us a stream-of-consciousness perspective which only further confuses the matter. The third person narrator will set up a scene, then Sebastian will take over. Then it will be a slew of out-of-context ramblings which you'll either enjoy or you won't (this is yet another book where I instinctively recoiled at the idea of stream-of-consciousness but ended up actually enjoying it). Overall, it kinda works and gives you a Joycean sense of swirling drunkeness.

Sebastian is the stand-out character but I did enjoy Mary and her veracious appetite for sex. Her descriptions and wordings are immensely entertaining. You can understand why it was banned on publication in the mid '50s (though fairly tame by modern standards).7/10

-

The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984) Milan Kundera

A narrative which spirals around a Czech couple named Thomas and Tereza in the late 60s/early 70s. Despite openly being a womaniser, Thomas (a doctor) and Tereza (a young photographer) find themselves in a serious relationship, eventually getting married and even owning a dog called Karenin. Tereza tolerates his infidelities, even understands his justifications for them, and even befriends one of his lovers Sabina. The book momentarily goes off on a tangent where we explore Sabina's life and that of her lover, Franz, before it returns to Thomas and Tereza.

The novel delves into philosophy and meaning, the narrator (Kundera himself) occasionally acknowledging that these people are merely characters serving a purpose. When he refers to himself, it initially seemed like he was a character narrating the book, but gradually you come to understand that it's just Kundera telling us (openly speaking to the reader) about these people's lives. This allows him to meander on various ideas and thoughts. Essentially, this is a snapshot, a fleeting peek into the lives of two people (and two more whose lives are touched by them) during a period of political upheaval (Russians invading), and personal happiness. The narrator tells us their eventual fate then returns to the story, jumps ahead in time, goes back to their childhoods, moves around their lives to give us more insights. My own particular favourite period is when Thomas -- blacklisted from working as a doctor by the communist regime -- works as a window cleaner and has a series of sexual adventures with numerous women. It all felt very 'Confessions of a Window Cleaner.'

The writing is wonderful and the chapters are short which (for me at least) encourages one to continue reading. This book is neither character driven (since we get very little of their actual characters) nor plot driven. It is a momentary glimpse into the lives of a handful of human beings doing and being what all other humans have done and been. There is a lightness to that being. It comes and goes so quickly. It hurts. It fills us with joy. And when our dogs die, it is unbearable.

A unique work.8/10

-

Even with a large user base, a book forum isn't really conducive to debate or discussion. Because ideally, you need to have read the same books.

Which is why I think a 'like' button makes some sense. You can engage with a post without necessarily needing to offer an opinion. Good for lurkers.

-

The Conformist (1951) Alberto Moravia

As a young boy, Marcello feels different, to the extent that it concerns him. Before he has a chance to properly analyse any of these feelings, he has a traumatic experience which will define him for the rest of his life. He comes to the conclusion that the only method for dealing with his confused state is to fit in and be normal. As an adult he explores what it means to be normal, does everything he can to look, sound, and behave in ways that, he believes, will ensure he is convincing. But of course, it's an act. And one which has conflated 'being normal' with merely 'conforming.' As such, in a society where fascism is the norm, he understandably becomes a fascist. He dresses smart, speaks with a measured assurance, marries a nice girl, and does his duty.

The plot revolves around Marcello, now working for the secret police, using his honeymoon as an excuse to visit Paris so that he can point out an old university professor to his colleague Orlando; Orlando's mission of course is assassination. But when he meets the professor's wife, he is overcome with not just attraction to her but, in his words, genuine love for her.

As with 'Boredom' and 'Contempt,' I was absolutely captivated by the writing. There's just something immensely engaging about it. I probably enjoyed this less than those two for two reasons: 1) it was a third person narration and though very good, it lacked the personal worldview of the protagonist which I loved in Boredom and Contempt; and 2) the sudden moment of overwhelming attraction (which he describes as love) that Marcello has for Anna. This comes out of nowhere (as does Anna's lesbian affection for Marcello's wife). It all felt slightly over-the-top despite the theme which might justify it (namely Marcello's inability to adapt and cope with ethical dilemmas that contradict his supposed grasp of normality). That aside, the book was enormously entertaining.

The ending was bitter sweet. His encounter with the ghost of Lino (vague and disturbing) producing the most captivating theory of the book: that loss of innocence is the only true normality. But (rather curiously) as with Boredom and Contempt, there is a incident in a car which seemed excessive. But it's a small complaint.8/10

-

Ah, that makes sense, I'll just do that. Cheers.

-

Do we have a book lists thread here?

Given that Book Group is closing on the 6th, and I quite like logging what I'm reading (without having to scroll through my book blog), it might be a good thread to have as a sticky.

-

The Bell Jar (1963) Sylvia Plath

The story of a young 19-year old woman named Esther Greenwood who begins the novel as an intern at a women's magazine whilst staying at a women-only hotel called the Amazon. Esther reminisces about her short life thus far and slowly seems to be overwhelmed by a creeping ennui until eventually she becomes obsessed with the idea of committing suicide. After one such failed attempt, she ends up in an asylum and continues to evaluate her life (and her desire to lose her virginity).

I enjoyed the book a lot but especially the periods where she thinks back to her burgeoning romance with Buddy Willard; those chapters were more engaging and it felt like a narrative was forming, a theme, but this was later dispensed with as the story began to focus more on her time in the asylum. Truth be told, those later chapters (which stuttered and were disjointed) were the least interesting thing about the book. Her brief sojourn with the guy called Irwin and the blunt way that Plath details Esther losing her virginity was the only part of the latter half that intrigued me. I found the first half of the book, where she reminisces about her life and demonstrates a lack of interest in the world (one which embodies an existential crisis), the most enjoyable to read. In those chapters, her mental health is a faint and subtle echo in the background. But later it's more transparent and relentless.

The writing is very good and Plath uses interesting turns of phrase which in another's hands wouldn't be as effective. Not perfect but very good.7/10

-

All the contemporary (prize nominated) books I've ever read have disappointed me. Like so much today, it seems that the author's identity is more important than the writing.

-

Embers (1942) Sandor Marai

This is a genre book (which I generally avoid). I'm not sure what the genre is but I suppose gothic suspense mystery might adequately describe it. The story takes place in a castle in a forest during the 1940s, but it feels a lot more like the 1840s (at one point the lightening knocks out the electricity and the castle is kept alight by candles). An elderly general named Henrik has received news that an old friend (Konrad) is to visit him at the castle that evening, a friend that he has not seen in 41 years. The staff are given instructions to tidy the place up and prepare a meal. In the meantime we get some backstory about how these two friends met as young boys, became best friends in military school, and spent the next twenty years of their lives entwined as brothers. But then something happened causing them to part and this is what is to be discussed once his friend arrives.

I enjoyed this a lot and found it very easy to read. The first half of the book is a third person narration but the second half is almost entirely dialogue (and almost exclusively from the general). Each chapter goes by very quickly as the mystery element builds. It doesn't take long to figure out what's going on though. The enjoyment is less about the mystery and more the writing combined with the atmosphere it generates (the empty castle alight with candles as a storm thunders in the background is always fun).

I immediately thought this would make an excellent play and (having googled it) have discovered that it was indeed turned into one. Given that it's essentially two characters (with a few background servants) I think it would suit that medium perfectly.

It won't necessarily live long in the memory (plot driven genre books rarely do with me) but if that's your cup of tea, you should like this a lot.7/10

-

Contempt (1954) Alberto Moravia

Riccardo and Emilia Molteni have been married for two years. They were very much in love to begin with but now, with a new home to pay for, and a job he doesn't enjoy (working for a film producer named Battista), in order to pay for it, he finds that she is becoming quite distant from him. At first he doesn't think much of it but gradually comes to believe that she no longer loves him. Initially, she denies this but then, after a heated argument, confesses that it's true but more than that -- she not only doesn't love him but in fact despises him. Understandably, Riccardo demands an explanation for her contempt but she doesn't have one or refuses to give it. Then Battista suggests a trip to his villa in Capri to prepare for a movie of the Odyssey and things come to a head.

As with 'Boredom' the writing is wonderful and Moravia speaks to me in a way that few other writers do; there's just something about his style that I find immensely easy to read and so fluid that each page melts away. Even when the subject matter is ultimately quite mundane (the breakdown of a marriage) it is utterly compelling, and dare I say it, even nourishing. The whole narrative is fresh and flowing like a cool breeze by the sea, never jarring or stunted, always lyrical and clear (and least to me).

*spoilers*

The story is straight-forward but for one aspect that confused me; namely, the reason why Emilia has suddenly stopped loving her husband and claims to despise him. Moravia leaves confusing clues regarding her affair with Battista such as when Riccardo encourages Emilia and Battista to share a car and she shows obvious discomfort at this, almost as if she is trying to tell her husband that Battista is sexually harassing her. Then later, in a similar fashion, Battista suggests that she come in his car while Riccardo goes with the German director, and once again she is hesitant, clearly demonstrating that she does not want to be left alone with Battista. All of this suggests she is an unwilling (even potentially coerced) participant but at the end of the book, she decides to leave with him (admitting that she may even become his mistress claiming she is "not made of iron"). I'm not entirely sure if it was Moravia's intention, but I was as bewildered as Riccardo.

It didn't fascinate me quite as much as 'Boredom' but it came very close. I've already ordered 'The Conformist.'9/10

-

Demian (1919) Hermann Hesse

A boy discovers that Christianity doesn't have all the answers and that there is a duality in the world of light and dark. He meets a young man named Demian who appears to encapsulate these transgressive thoughts and becomes enchanted by him and everyone else who has opened their eyes to the truth.

The writing is fine and goes along nicely (especially the last few chapters) but I couldn't help but feel that I was being lectured at by Hesse about his hippy spirituality. And this is the third time he's done this to me. In Steppenwolf (also about the two sides of humanity) it was forgivable because that book was so engaging, with a narrative which meant the magical stuff felt earned. Then he did it again in Siddhartha but that was entirely about spiritual enlightenment so fair enough. Knowing that he does this a lot has, however, slightly tarnished my memory of Steppenwolf and made Hesse seem like a rather one-note bore (I hope that isn't the case). As much I enjoy being told about the magical ideas of the ancient world, there does seem to be a mild fetish going on here with him. And hiding it behind ethereal notions of vague telepathy and obscure Hindu myths doesn't do much for me either. At one point, Hesse even talked about the herd (like some teenager in his basement calling other people on the internet 'sheeple'), and I frankly wasn't very impressed by that whole... we see things differently. In all honesty, Hesse and his wooly spiritualism are the least interesting things about him for me.

By the end, Demian's mother simply came across as a cult leader with an unhealthy interest in younger men. I guess you have buy into that spiritual stuff to find such things profound or intriguing. With Steppenwolf, it worked, but not here. The book is short, though and, like most of Hesse's work, well written.

I would still recommend it.6/10

-

Blindness (1995) Jose Saramago

A man is stuck in traffic and suddenly goes blind (a milky white blindness as opposed to darkness). A good Samaritan takes him home only to later steal his car. The next day he sees the doctor who is baffled. The day after that, the doctor discovers that he is now blind. And on it goes, with more an more people discovering that they are blind until the government starts rounding them up and placing them in an asylum. To begin with there are forty to fifty but gradually the numbers drastically increase. The doctor's wife also claims to be blind to stay with her husband despite this not being true. The army are positioned outside with strict instructions to shoot anyone who tries to leave. Soon the place is overpopulated with excrement everywhere and dead bodies. Then a group in a separate wing decides to keep all the food for themselves and demand money and jewels for food. Soon, they switch and demand that females from each ward be sent as payment. Eventually, the army abandon post as the blindness epidemic continues and the small group leaves and roams the apocalyptic streets in search of food and shelter.

The allegory here is fairly obvious, concerning the true nature of humanity and how civilisation has a tendency to ignore what's in front of their eyes. But I found that fairly simplistic and predictable with little originality. Most of us know exactly what humanity is. Most of us keep that truth close to the front of our minds on a daily basis. There is nothing especially groundbreaking here and in truth the high praise this book receives is slightly bewildering to me. I get the impression that it's a lot of people who want to read Stephen King but also want to seem more intellectual (Saramago won a Nobel prize after all).

That being said, I enjoyed the book and was swept along at a decent pace; the story is very engaging and though the writing style is often chaotic (very few full stops), it's actually quite an easy to read. My only criticisms would be the oppressively long chapters which, more than once, had me craving that they would end (never a good sign). And I also disliked the doctor and the girl with glasses having sex; it seemed absurd and pointless, and strangely presumptuous of a male writer.

Overall, very good though.7/10

-

Hangover Square (1941) Patrick Hamilton

There's a modern term that's used to describe men who pander and flatter women in the hopes that they'll be rewarded with love, sex, attention. Simp! And this book is about the king of the Simps -- George Harvey Bone. He is in love with the beautiful Netta and hangs around with her and her set, drinking at all hours and avoiding employment of any kind. He confesses his love for her but she continues to use him for his money and, later, for his connections. One of her hangers-on is Peter, a spiv character who is just as keen to take advantage of George as she is.

I honestly found myself despising Netta quite viscerally but also George too, his unwillingness to grown a spine despite being treated like a doormat something that infuriated me. The book reminded of the Tunnel by Sabato but whereas the paranoia of that book's male protagonist could be interpreted as self-inflicted, there is no ambiguity about George's feeling of humiliation and poor treatment. Netta is, quite explicitly, a bitch. She has a past working as an actress and has aspirations to get back into that world but otherwise she is, like the men she consorts with, a self-interested alcoholic. And George is nothing more than a means to an end for her.

And here's where things get complicated because George, also a big drinker, suffers from a unique mental illness. I would describe it as a dissociative personality disorder but it's all a little vague. Essentially, it involves George going into a kind of dream state where an alternative version of himself is in control of his thoughts and actions. When George clicks in and out of these personalities, he remembers very little of what has happened. The whole thing is very effectively done by Hamilton and you get the impression that George is just one person but has two states of being.

The book also takes place just as the 2nd World War is about to begin and I found it fascinating seeing these young people presented in a manner that was very familiar to me. When I think of that period, I think of straight-laced individuals wearing starched clothing and doing their bit for the war effort. But obviously, young people were just the same as they've always been; keen to get drunk, have fun, and avoid work. That the book was published in 1941 at the height of the war is also interesting as Hamilton essentially takes it for granted that fascism will lose.

This was a great book. And very uniquely British.8/10

-

Stoner (1965) John Williams

I've been hearing a lot of hype about this book for some time. The copy I bought even had the words 'the greatest novel you've never read' on the front cover. I think those days are over. This book is now a hipster's wet dream.

Firstly, it's beautifully written with some exquisite turns of phrase. Secondly, it's a story that will utterly pull you in. A story about a man's life passing him by (because that's what most lives do). He leaves his farming parents behind, goes to university, marries, becomes a teacher, has a daughter, has an academic rivalry, watches two world wars come and go, has an affair, becomes middle-aged, gets cancer.

All the while, you feel as though Williams is trying to say something about passion, about the ability to communicate your feelings. This is presumably why the book is written in third person (when such a narrative suggests a first person perspective would make far more sense). He wants Stoner to be a little detached from us, to be cold, stoic, unemotional. But he also wants us to know that Stoner wishes he could overcome that flaw, could demonstrate love for his wife and daughter, for his work. Stoner tells us (more than once) that he can't quite adequately communicate the passion he has for English literature to his students (but it seems evident that he doesn't entirely try either). Perhaps Williams is saying something about the times. It would seem clear that he's criticising it (and yet, paradoxically, I long for the culture he laments and find the endless sharing of feelings we have in the modern world to be thoroughly repugnant). His wife, Edith, also suffers from this same malady, perhaps more so. She is even more emotionally closed off and seemingly struggles to share any moments of sincere joy, an affliction which their daughter begrudgingly inherits. It's only Katherine who provides Stoner with any such fleeting possibility of fulfillment.

It's all dreadfully sad. Stoner is no-one important and yet his life still matters. It is still worth knowing about. As the book tells us on the opening page: 'Stoner's colleagues, who held him in no particular esteem when he was alive, speak of him rarely now.'

One can't help but feel that this probably applies to his family and friends too. In truth, this might be the best novel I've ever read about life being both pointless and meaningful all at once. I would give it a higher rating but for the fact that it occasionally manipulates the reader, utilising techniques which are nonetheless subtle and enormously entertaining to read (like when Spielberg wants to make the audience feel something, he'll use music to provoke an emotional response).

That aside, I thought the book was wonderful.9/10

Article on Céline (separating artist from the art).

in Book News

Posted

Interesting article on Céline and separating the artist from the art.

"If we demand that our artists be angels, we will not have any art left to appreciate."

https://quillette.com/2022/07/11/celine-literary-antichrist/