-

Posts

3,501 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Books

Everything posted by willoyd

-

11. Not A River by Selva Almada ***** Much as I'm loving Ulysses, it's a book that I think I'm going to need the occasional break from, and this is the first! Reading various articles on publishers of books in translation (particularly a Guardian profile piece on several UK indie publishers), my eyes picked out this book from Charco Press in a tabletop display in my local Waterstones during a browse earlier this week. I've not read any of their books yet, but the name was familiar from the articles. A quick glance, and I knew I was hooked, not least by the production values (I'm a sucker, especially, for French flaps!). I've since discovered it's on the longlist for this year's International Booker and, having read it, I'm not surprised. At only 99 pages (including a fascinating translator's note), this was a short but absolutely compulsive read: two friends are on a river fishing trip with the teenage son of another friend who died on a previous visit. They successfully land (by shooting!) a monster ray, which attracts the attention and the ire of local villagers, threatening as the book progresses to boil over in violence. The story tells of how the relationship pans out, with flashbacks centred both on the fishermen and the villagers' lives fleshing out both how they got here, and why things work out the way they do. It's a carefully, tightly woven narrative, made all the tighter by Almeda's very lean language and the spartan use of punctuation and paragraphing. So often this latter makes life harder, but the author's style rapidly grew on me, and it really did add to the atmosphere and my involvement as a reader (I may have been helped by the fact that I'm a few hundred pages into Ulysses, which has similar traits that actually made this feel relatively easy!). Almeda's focus is primarily on aspects of masculinity, much toxic, in a strongly patriarchal society, and some of the fallout from this, with this being the third in a thematically related trilogy of books (they each stand alone, with no narrative or character crossover, so don't need to be read in order). Yet, whilst the questions are asked and themes aired, this is also, in its simplest terms, a brilliantly told story, with a twist that both took me utterly by surprise, and made me go back to reread whole sections (easy enough when there's only 99 pages!) to tease out the clues, indeed large bites of narrative meaning, that I'd missed. This was a book which produced a genuine "Oh I see it now!" moment well after I'd reached the end. Maybe (probably!) I'm just a bit thick, but I did enjoy the revelatory experience! So, a very happy impulse choice (perhaps not the right word, as this is a very dark book!), and a great one for Argentina, the 37th country to be visited in Reading The World.

-

Your Book Activity 2024

willoyd replied to lunababymoonchild's topic in Book Blogs - Discuss your reading!

Having finished The Sorrows of War, and Benjamin Myers' The Offing, have moved on to the next big one, perhaps THE big one, Ulysses. About 150 pages in, and whilst it's challenging and I'm glad of some help from a reading guide and an annotated edition, I'm loving it. We'll see how it develops. -

Currently reading the big one! Could well not be posting much over the next month or so, as have at last got stuck into a book that have been intending to get to grips with for some time now, my choice for Ireland in Reading the World - the almost inevitable Ulysses*! Am around 150 pages in (Leopold Bloom has just arrived at the cemetery). Am being helped along by Patrick Hastings' The Guide to James Joyce's Ulysses, which has a useful summary of each episode, which I'm reading as a follow-up - and it does help. I've also got one of the annotated versions on my Kindle, and that's been really useful too understanding some of the references, although one could get hopelessly bogged down if checking out each one! But even before using these, I'm starting to find it utterly addictive. In places it's almost hypnotic in its rhythms. It's particularly picked up since Leopold Bloom appeared (in section 4, Calypso) - his internal narrative is rather more down to earth than Stephen Dedalus's and have almost instiinctively warmed to him. If anything (and only so far!) have found it an easier read than expected, although section 3 (Proteus) left me gasping rather especially at the start. It's going to need a reread though, I can already see that!! In the meantime, I had expected that I might need to intersperse with some lighter reading and that I would likely have to be quite structured/organised in my reading to get through, but at present, I'm loving the exploration and positively wanting to pick it up and get stuck into the next bit, so we'll see! *In fact, Ulysses was from the word go, at the heart of the project, as set it as the baseline, the earliest, book that could be read. I started Reading The World in 2022, the centenary year of the book's publication, and it was the first book I chose for a country. Sort of made sense that books should come from the last 100 years - or at least in the years since Ulysses was published.

-

10. The Offing by Benjamin Myers ***** We're reading a Myers book for my next book group (The Perfect Golden Circle), but as I've read it before (I may still reread) I decided to try one of his that I hadn't read. My local indie shop owner, knowing I was after something a bit lighter, suggested this. Spot on! It's an elegiac look back by the narrator, Robert, to a time just after the Second World War when, as a young man on the cusp of moving from school to the mines in his Durham coalfield village, decides to 'take off' for a few weeks in the summer to explore the world around him on foot. He lands up in Robin's Hood Bay (on the North Sea coas)t, and meets up with and develops a friendship with an older woman living on her own. It's a Bildungsroman, but aside from that, reminds me very much of perhaps my favourite book, A Month In the Country, as in both the (young male) narrator's character and relationships develop over an English rural summer with a quietly powerful long term impact on their life. - it's not quite there, not being as nuanced, nor with quite the variety of tone and he plot development that was part of what marked AMITC out, but it was a beautifully poetic read with an interesting development, that I can see myself going back to. Benjamin Myers is an author who is gradually growing on me - he's not (so far anyway!) spectacular or showy (although I'm told that a couple of his books that I have yet to read are very different), but quietly gets under your skin. An initial five star read,but could easily get kicked up a level later. (BTW, 'offing' is apparently the name for the distant part of the sea that's in view - the part where the horizon meets the sky).

-

Book #36: The Sorrow of War by Nao Binh for Vietnam ** A classic of the Vietnamese war I understand, on a par with All Quiet on the Western Front and other war greats. I can see sort of see why, but personally I found this a tough, unrewarding read, boring me rigid before I reached half way, and struggling to make it to the end of what is, after all, only a slim 220 pages or so. Graphic in detail (the even mildly squeamish should be wary), unrelenting in its grimness, it may well be an all too starkly accurate portrayal of what the war was like, but I also found it repetitious and narrow in its language (this, of course, may be a function of the translation), equally repetitious in its narrative, and disjointed in its telling - chronological this is not (I don't normally find this a problem, but on this occasion it just confused). The odd attempt at metafiction just felt clumsy. All of this, for some readers (actually, most readers from the reviews - I'm definitely in a minority here) may well add to the impact, or carry this into the realms of the classic, but I'm afraid it just lost me about a quarter of the way in, and with only occasional remissions, it remained that way to the end, by which time I was really having to force myself not to leave it unfinished (I'm really trying to ensure I read books all the way through for this project, even if it's one I'd normally abandon). I'm sure this is down to inadequacy as a reader on my part, but this was a book I was glad, relieved, to put behind me.

-

09. The Sorrow of War by Nao Binh ** The book for Vietnam in my Reading The World project. This is a classic of the Vietnamese war I understand, on a par with All Quiet on the Western Front and other war greats. I can see sort of see why, but personally I found this a tough, unrewarding read, boring me rigid before I reached half way, and struggling to make it to the end of what is, after all, only a slim 220 pages or so. Graphic in detail (the even mildly squeamish should be wary), unrelenting in its grimness, it may well be an all too starkly accurate portrayal of what the war was like, but I also found it repetitious and narrow in its language (this, of course, may be a function of the translation), equally repetitious in its narrative, and disjointed in its telling - chronological this is not (I don't normally find this a problem, but on this occasion it just confused). The odd attempt at metafiction just felt clumsy. All of this, for some readers (actually, most readers from the reviews - I'm definitely in a minority here) may well add to the impact, or carry this into the realms of the classic, but I'm afraid it just lost me about a quarter of the way in, and with only occasional remissions, it remained that way to the end, by which time I was really having to force myself not to leave it unfinished (I'm really trying to ensure I read books all the way through for this project, even if it's one I'd normally abandon). I'm sure this is down to inadequacy as a reader on my part, but this was a book I was glad, relieved, to put behind me.

-

Your Book Activity 2024

willoyd replied to lunababymoonchild's topic in Book Blogs - Discuss your reading!

Just finished The Marriage Question by Claire Carlisle, and have now started The Sorrow of War by Bao Ninh (Reading The World project book for Vietnam) -

08. The Marriage Question by Claire Carlisle **** Read as a follow up to Daniel Deronda, this is a biographical study of George Eliot's life with George Lewes and, to a lesser extent, John Cross after Lewes's death. It's also as much a study of the influence of her 'married' life on her novels. It's an enthralling read, providing considerable insight, and I feel I learned much about both Eliot's life and her writing. Inevitably, I found the chapters covering Deronda and Middlemarch, my most recent and favourite George Eliot books, the most interesting, but the rest was never less so, and I came away keen to both read further and reread (although twice through Silas Marner may be enough already!). Carlisle is a Professor of Philosophy at KCL, and this was transparently obvious in her writing: aside from her extensive discussions on Eliot's philosophy, there's even a chapter so entitled. I have to admit however, that she lost me on occasions, and there were one or two points where I glided rather bemused over the surface for a couple of pages, but the book soon retrieved me the other side. I readily admit that this is almost certainly down to my intellectual failings - I am certainly no George Eliot on that front, as she sounds to have had a formidable mind - the depth of knowledge she insisted on developing on each subject before she wrote on it was remarkable. I was, in contrast, surprised, having long felt that she was something of a feminist icon (she still is IMO, but in a different way perhaps!), as to how much she conformed to the Victorian model of a wife's role with both Lewes and Cross, even if, in Lewes's case, she was strong enough to continue their relationship openly unmarried. Their relationship may not have been acceptable to Victorian society as a whole, but their was still something very upright in the Victorian manner in the arrangements between Lewes and his two partners, once one scratches the surface. Overall, then, an involving, illuminating read, which has encouraged me to further develop my acquaintance with Eliot's novels (perhaps Adam Bede next?) and to read further on the full extent of her life - I have the Rosemary Ashton biography on my shelves, so that's a distinct possibility later this year.

-

07. Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout **** The book for Maine in my Tour of the USA. I originally had Richard Russo's Empire Falls down for this, not least because I'd be somewhat underwhelmed by my previous effort at a Strout novel, My Name is Lucy Barton, but a book group discussion (where I was in a minority of one in my views on the author's work!) encouraged me to give her another go - and given the success of this book (Pulitzer Prize winner) it seemed the obvious one. It's construction is also one that intrigued, the novel being formed from 13 short stories. Well, I'm very glad to have read Olive and, whilst I can't say I have been completely converted, it was certainly a far more rewarding experience than the one with Lucy Barton. Or, perhaps, 'appreciated' would be a better word, as books as downbeat as this are rarely 'enjoyable'! It's certainly beautifully written: I was caught up in the writing from the outset, and loved the little details, the turns of phrase and the internal monologues; characters and place were strongly wrought. I found the development of Olive herself particularly fascinating, the way she ran as a thread through the 13 stories, sometimes the main character, rather more often introduced sideways, almost a cameo on occasions. The themes of older age, personal isolation (even when surrounded by others), and contrasting perceptions and experiencing the same events, also added to the coherence and interest, making me sit back after each story and reflect on what I'd just read. Characters were not necessarily likeable (far from it - there weren't many that were in fact, including Olive herself), but they were interesting. And yet, and yet...whilst this worked for me as a collection of connected short stories, it didn't quite make it as a novel in the same way that, for instance, Jonathan Escoffier's If I Survive You did. Whilst there were elements of connection, in the end the stories themselves were just too fragmented to create the coherence that a novel needs. That fragmentation was created in a a number of ways, none enough on their own, but together too much. Firstly, the chronology is out of sequence. This in itself isn't a major issue, but when you read in the first story that Olive's husband Henry has retired, and then in the second story that he's thinking of retiring, it just jolts one out of immersion, prompts checking and questioning before settling (slightly uncertain) back in, and leaves one never quite trusting the thread of the narrative after that. It might be a set of short stories, but it's also a novel, and whilst plenty of novels use time shifts etc (often to advantage), there's a reason, and here there seems to be no good reason for doing so. Secondly, the characters are too fragmented, or at least isolated. The Kitteridge family provide some continuity, with Olive, Henry and son Christopher appearing throughout. One or two other characters appear in more than one story, but in general, once a person has been written about, they largely vanish. Given that this is meant to be a relatively small community (or at least that's the impression), that just didn't work for me - I'd expect people to appear and reappear. It also proved unsatisfactory. If you're going to have a dramatic event in a novel, then one expects, indeed wants, to learn something of the outcome of that event. You just don't have one, and then no mention of it or those involved ever again. Finally, there's the repetition. In several later stories we are told things that we already know about: we've read all about them only a story/chapter or so earlier. The copyright page tells us that several of the stories have been published previously (over a 15 year period), which is fine, but if they are now being brought together as a novel, then they need editing and co-ordinated. There was also a feeling of sameness to several of the stories - we are dealing with different people (by name), but rather too similar characters/scenarios? The disjunct between novel and short stories was also driven home by the fact that for a small community, there's an awful lot of drama: murder, hostage taking, suicide (more than one), accidental killings, along with all the other life threatening natural hazards of life. It's not quite Midsomer but it still seems a bit OTT, and maybe lent to that sameness feeling? Never mind being downbeat about old age, I think most would inhabitants of Crosby, Maine, would be grateful, even relieved, to make it that far. I think that's partly because one piece of such drama in a short story is fine - it works, it's what the story is centred around. But drama after drama, in each chapter, is too much for a novel. The result was that, whilst some of the drama worked well for me early on, by the second half of the book,I was grateful for the stories focusing on the domestic. However, whilst I feel I've focused rather on the negatives, in the greater scheme of things they are rather more blemishes than deep seated faults. I found so much of this compulsive reading, not least the character of Olive herself. She's obviously not immediately likeable, if at all, but there's a humanity to her that gives her huge depth, and makes you wonder quite what you would make of her yourself. There's an ongoing thread around her relationship with Christopher that raises all sorts of questions, discussion points, issues of witness reliability etc worthy of a whole book on its own, never mind everything else - it's superbly handled by the author, and is one of the most thought provoking threads I've read in fiction for some time (not least because it's so relevant to aspects of my life). So, an intriguing book (I rarely write as much as this in review), stronger if regarded in its raw form as a collection of individual short stories. I certainly intend to try out more of Elizabeth Strout, and more specifically re-examine Lucy Barton. She may not be a 'favourite' author, but is one that is has made me think, and I'm interested to see what I make of some of her other work.

-

Book #35: The Bone Readers by Jacob Ross for Grenada ***** The book for Grenada in my Reading The World project. I don't often read crime fiction, although I am a fan of both Simenon (Maigret) and Leon (Brunetti), and have enjoyed a fair few others (admittedly usually historical fiction, like CJ Sampson). However, this appealed from the word go, and in the event didn't disappoint. As with all the best crime fiction, it's so much more. Yes, it has a good plot (and this is not cosy crime, having corruption, child abuse and statutory rape at the heart of the problem), but that's not what makes a book for me. What I enjoyed were the strongly drawn characters (both male and female), the sense of place (a major part of why I so enjoy Simenon and Leon), and the insights into island culture and politics. The author tries to reflect the local patois in his dialogue, and yet still manages to leave it eminently readable and understandable, only demanding a couple of rereads when I realised I'd misunderstood something! In short, I find this pretty much unputdownable, reading into the early hours to finish off last night - that doesn't happen often with me! And, as a confirmation of how good I thought this was, I've already ordered Ross's other two novels from my local bookshop. Whether it gets upgraded to 6-star/favourite status later, time will tell, but in the meantime, this is an easy 5-star grading.

-

06. The Bone Readers by Jacob Ross ***** The book for Grenada in my Reading The World project. I don't often read crime fiction, although I am a fan of both Simenon (Maigret) and Leon (Brunetti), and have enjoyed a fair few others (admittedly usually historical fiction, like CJ Sampson). However, this appealed from the word go, and in the event didn't disappoint. As with all the best crime fiction, it's so much more. Yes, it has a good plot (and this is not cosy crime, having corruption, child abuse and statutory rape at the heart of the problem), but that's not what makes a book for me. What I enjoyed were the strongly drawn characters (both male and female), the sense of place (a major part of why I so enjoy Simenon and Leon), and the insights into island culture and politics. The author tries to reflect the local patois in his dialogue, and yet still manages to leave it eminently readable and understandable, only demanding a couple of rereads when I realised I'd misunderstood something! In short, I find this pretty much unputdownable, reading into the early hours to finish off last night - that doesn't happen often with me! And, as a confirmation of how good I thought this was, I've already ordered Ross's other two novels from my local bookshop. Whether it gets upgraded to 6-star/favourite status later, time will tell, but in the meantime, this is an easy 5-star grading.

-

Thank you both - I'll do my best! TBH I find it personally useful - especially when I can't remember a thing about a book I read only a few months ago!!

-

05. Cursed Bread by Sophie Mackintosh *(*) I picked this up in our local bookshop as the premise intrigued me, being (apparently) based on a real incident in 1950s France, when an entire village (including animals!) succumbed to some form of (never identified) mass poisoning. On this, the author bases a 'darkly erotic mystery'. There was certainly a lushness, an elegance of writing that initially drew me in, giving the book an instant appeal, but after the (promising) first twenty pages or so when the two principal couples are introduced and developed (baker and wife with non-existent sex life, he obsessed with the 'perfect loaf'; metropolitan 'ambassador' and wife Violet, interesting sex life, a source of increasing obsession for the baker's wife Elodie) things started to deteriorate. The whole sexual aspect felt increasingly unlikely and contrived (and disjointed), whilst the the only mystery for me was a growing sense of confusion, wondering what on earth was going on, and had the author lost the plot (literally)? The story, mainly told in the first person by Elodie, interspersed with letters to Violet from Elodie written long after the events being described, felt increasingly disjointed and engendered irritation rather than intrigue (morsels of the outcome being dripped into the story by these letters). Relationships and plot progression just became more and more obscure, especially as one was never sure if Elodie was fantasising, recounting fantasy, or actually giving us the reality; there's unreliable narrator and unreliable narrator! To be honest, I found this easier and easier to put down and harder and harder to pick up; in short, I was bored, this coming over increasingly as more an exercise in style than a piece of narrative fiction. I finally forced myself to sit down and read the last 60 or so pages (it's only 180 pages long) in one sitting, as I realised I simply wasn't going to reach the finishing line otherwise. And when I got there? Nothing, or at least little of any consequence or interest to this reader. In fact, a thorough anti-climax, particularly in relation to the mystery that wasn't - because the mystery I was interested in is what happened over the mass poisoning (touched on throughout), and that really wasn't what the author was interested in after all. Yes, the 'darkly erotic' bit was resolved, but then I'd never found that interesting (and certainly not 'erotic'). In one phrase? Elegantly tedious. Not sure whether to give this one star, or allow a second for the writing, because strictly speaking the ending took it beyond being just 'disappointing' (2 stars) into the genuinely unlikeable (1 star).

-

04. Daniel Deronda by George Eliot ***** Read for one of my book groups. Having said that, this has long been on my to read list, and I was grateful to be kickstarted to actually read this huge tome - by far and away the longest book I've read in the past few years, coming in at 900 pages in Everyman Classic edition (and just over 1000 pages and 2 volumes in my 1930s Collins Clear Type Press edition!). Right from the outset, I would say that it's not (IMO!) quite in the same league as Middlemarch, but it is a powerful, intricate, fascinating read, that never lost my interest in the 3 weeks or so that it took me to read. In many respects (and it's often claimed to be as such) it's almost two books rolled into one: the story of spoiled, almost childlike, Gwendolyn Harleth and her marriage to perhaps one of the nastiest characters in fiction, Henleigh Grandcourt, and that of Daniel Deronda, foster son of Grandcourt's uncle, Sir Hugo Mallinger, and his search for self-identity. Indeed, it has been argued that the book(s) would have been better if separated, one critic (FR Leavis) in particular arguing that if it wasn't for the burden of the latter story, the former would be one of the great classics. Hmmm. I can see where this comes from, but the fact is that the two parts are integral to each other for the whole book. Gwendolyn and Deronda are foils for each other's development (although Gwendolyn is initially so self-centred that she barely notices anything else Daniel might be doing or thinking), and Gwendolyn and Mirah are important foils to each other in their relationship with Deronda. And how would Leavis handle Daniel's 'journey' if cutting out his relationship with Mordecai? On the other hand, there have been many (mostly interested in the Zionist aspects) who would discard the Gwendolyn thread. Ridiculous! But, I can understand where these arguments come from. With two major plot lines, each in itself worthy of its own book, it's not surprising that this novel is so big. It's thus all too often encumbered (and yes, I'm afraid it does feel that way at times) with having to cut away from one narrative thread to deal with the other: the two only really come fully together in the final hundred and fifty pages or so (when the action transfers to Genoa), only nudging up against each other at varying points in the previous 750! But, having said that, I did find watching the development of these two very different characters absolutely fascinating. What I think is easy to forget is how radical this book must have been at the time of publication, with Eliot's Jewish plotline, a time when anti-semitism was almost engrained in English society - it was certainly not appreciated by a fair proportion of her readership. My biggest regret though on this side is that Mirah, so central to the novel, is so thin as a character, particularly alongside the superbly developed Gwendolyn. We see into the heart of the latter, whilst we barely scratch the former's surface - too good and sweet by half. It often seems that way in Victorian fiction: it's the flawed, or worse, characters who are best developed, whilst the 'goodies' (especially the women) are so often left to be mildly uninteresting or at best over-sentimentalused. One of the strongest characters in this book is Grandcourt - the portrayal of his subjugation of Gwendolyn is brilliantly delineated, a classic case of isolation abuse, exploiting to the full all the advantages of the husband in Victorian society - a fair amount left to be read between the lines. Daniel Deronda was not an easy read, but it was gripping. I initially found myself having to plan to read a set number of pages each day to ensure I finished the book in time. In the event, as the book progressed, I didn't need to worry with that, as I found momentum building up. There were one or two sections where I found myself gliding over some of the more detailed discussion, especially on philosophical or religious topics, but on the whole I actually found myself hanging on to the words. With so much to discuss (I've barely scratched the surface above!) it'll make for a good evening. (And why is it, whenever I try to write a review of a half decent book, I really struggle to make sense? These reviews never turn out the way I envisage them, and I never seem to be able to write coherently about all the issues and questions these books raise).

-

03. Strong Female Character by Fern Brady **** Picked up on a whim in my local independent, having been grabbed by the first couple of pages, this proved an utterly compelling memoir. Fern Brady is a best known as a stand-up comedian, but the focus here is very much on her experiences growing up as an autistic female, undiagnosed until well into adulthood. It's a ferociously vivid read, doesn't pull any punches, and really shows up how far society as a while has to go in this aspect of life - we are not good at 'different'. I must admit, as an ex-primary teacher who taught two autistic girls in my last three years (one diagnosed, the other not, but blindingly obviously so) I wish I'd had the chance to read this beforehand!! It was an eyeopener, and particularly so where the author related her experiences / behaviour to the research into and recognised 'symptoms' of autism - and where she showed how those who should have known better missed the signs completely. What's really worrying is the strong implication that little has changed. I hadn't realised when I bought the book that it had been shortlisted for the Nero Book Awards Non-Fiction prize, but found out as I finished it, that it had actually won. I'm not surprised. Once or twice I felt it could have done with some stronger editing (a minor comment I hasten to add), but I am so glad I picked it up! (Book 02 this year was the York Advanced Notes, A Passage To India - which served its purpose well!).

-

Howards End is on my favourites list! Forster skewers the Anglo-Indian class in APTI as skilfully as he does the middle classes in HE! I don't think Adela was telling lies - she was telling it very much as she believed was true. Which is why, when she realised how wrong she'd got it, she changed her story, in spite of the personal consequences. I've just watched the film, and this comes across very well in that. But I agree, Howards End was more enjoyable. Both brilliant though, with ARWAV very close behind IMO. The more I read of Forster, the more impressed I am.

-

So, the end of the reading year. A good year on the whole. 66 books completed, the same as last year, even if the average page count was lower, but there were fewer disappointing books and a higher proportion of 4+ star books (mostly at 4 star level itself). A more detailed review on my 2024 thread.

-

Two last books Christmas Days by Jeanette Winterson **** A very enjoyable dozen stories with linking mini-essays that include some interesting recipes. None of the stories were earth shatteringly original or different to the standard Christmas fair, but then this is Christmas! They were still fun and, inevitably with this author, well written. I suspect I'll save this for future Christmas reads too, and certainly for a couple of the recipes! Frostquake by Juliet Nicolson *** Purporting to be a social history of the snow-stricken 1962-3 winter and the impact it had on a changing society (or at least that's how I interpreted the blurb), this proved to be a readable but ultimately disappointing mish-mash of personal memoir and general cultural history of the the period, spreading rather a lot away from the winter itself. Basically this was nothing that the likes of David Kynaston, Dominic Sandbrook, Peter Hennessy and others have all done so much better, and certainly more thoroughly researched and in-depth. It just about achieved 3-stars because it was readable, and it was both the last book of the year and the Christmas season, but 2 beckoned, ! However, it has gone instantly to Oxfam!

-

First post for 2024 - welcome to this year's blog. A good one to start the year off! 01. A Passage To India by EM Forster ***** Read for one of my book groups. I've previously read other Forsters, and enjoyed them enormously (especially Howards End), so was looking forward to this, and was not disappointed. Written in 1924, and very much an examination of the interaction between British and Indian in the India of the time, some twenty years before independence. On the whole we British don't come out of it very well! The full range of attitudes is represented in early chapters where both British and Indians discuss the 'other side' in some depth, the attitudes then examined under the stress of the incident involving Mr Aziz and Adela Quested in the caves midway through the book. To cover all those viewpoints, Forster uses a surprisingly wide cast of characters, which I have to say I did find a bit confusing at times (plenty of referring back to character introductions to be sure who was who!). This width did mean that some characters didn't feel to be drawn in any great detail, and the odd bit of stereotyping reared its head, but the central characters, their ambiguities and the dilemmas they faced, did come to life for me. As ever with Forster, he proved a far easier read than anticipated (I always expect these earlier 20thC books to be harder than they are, perhaps scarred a bit by some of Henry James's denser writing!), and I happily cantered through this first book of the year. It's also a book that I look forward to discussing in the group later this month - and one that I've also ordered a study guide for to try and tease out some more coherent thoughts. A final note - I found this particularly interesting because one line of my own family lived and was brought up under the Raj, if a bit earlier than the book is set - my grandfather was born in Delhi at the end of the 19thC and, whilst he came back to Wales at a young age, at least the two previous generations back to the early 19thC were out their all their lives (one great grandfather was in the Indian Army, another a teacher in India - which made the Cyril Fielding character all the more personally interesting).

-

But, contrary to my rather pessimistic post previously, the discounts are rather better than I predicted.

-

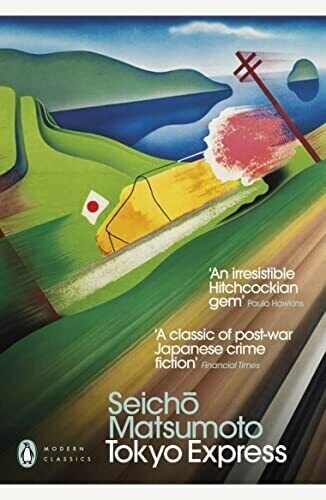

So, my awards are: Your favourite book cover of 2023: Tokyo Express by Seicho Matsumoto (see photo below) Cover based on a railway advertising poster. Penguin Modern Classics have produced a series of really interesting, attractive covers in recent years, and I could have nominated any number of these but this one definitely had an edge. Loved it! Your favourite publisher of 2023: Penguin Modern Classics A repeat award, as they were my winners in 2022 as well! Mostly as books for my Reading the World project, I've read a fair number of these this year. There are an increasing number of others publishing great books in translation, in attractive bindings, and I came close to nominating one of them, but these are the ones I've read and enjoyed most this year. Titles this year have included Tokyo Express, Potiki, Season of Migration to the North, The Year of the Hare, The Ice Palace, The Book of Chameleons, Who Among Us?, Chess Story. Your favourite book shop/retailer of 2023: Bookshop on the Square, Otley West Yorkshire Third year on the trot for my local indie bookshop. It's going to take a lot to displace them - maybe I should make the award for any other shop I've visited during the year! In which case, I'd probably go this year for The London Review of Books - one of my favourites in London which I was able to visit earlier this year. Your audiobook recommendation of 2023: none listened to this year Your most read author of 2023: Ann Morgan Another repeat award from last year: I've not read more than one book from any author this year, but I do keep referring to her website (one of the best online reading resources I know), her book on the subject, and her reviews of books in translation. Her new novel is on my shortlist to read this year. Your recommended re-read of 2023: none For the first time in years I've not reread a book this year. Your book that wasn't worth bothering with in 2023: Fates and Furies by Lauren Groff An easy choice this year, my only 1-star book. A book group read that was pretty universally panned. She's such a good writer too.... (I have both Matrix and Vaster Wilds to read on my shelves this year, so hopefully this is a one-off!). The book you most wanted to read in 2023, but didn't get to award: Ulysses by James Joyce I really thought I was going to get to this in 2023! It's my intended book for Ireland in my Reading the World tour, and as I didn't manage it last year, 2023 was going to be THE year. I'm hopeful that a couple of changes in circumstances will mean that I do finally get to it in 2024. Ther's a fistful of other biggies that have long been on the backburner too, so if I get any of them read this year I'll be chuffed! Your biggest literary let-down of 2023: jointly to Less by Andrew Sean Greer, and Demon Copperfield by Barbara Kingsolver Two Pulitzer Prize winners, and both books which completely underwhelmed me. The first was just poor and shallow to my mind - a series of silly episodes based on an unlikely premise. The second was more complex: I could see why people liked it, but for me it was just too derivative, and as a result one pretty much knew what was going to happen to characters before things happened. David Copperfield is one of my favourite reads, and this was just a shadow of it. Kingsolver is very much a marmite writer for me, and this was, of all her books that I've tried, my biggest let-down (whereas Poisonwood Bible was IMO superb). Your favourite illustrated book of 2023: none None read, other than history books with photos! Your children's book recommendation of 2023: none I'm not a great reader of children's books, and this was a year where I read none. Your recommended classic of 2023: La Curee (The Kill) by Emile Zola I'm reading Zola's Rougon-Macquart sequence in the order he recommended, and this was as good as any so far: I love the vividness of his writing and the depth of image he creates. His writing just brings that period to life. Your favourite short story (or collection of short stories) of 2023: The Garden Party and other stories by Katherine Mansfield Unusually, I read several collections this year, all excellent (I'm usually not a great short story reader), but this set showed why Mansfield is regarded as one of the great writers in the genre. I did rate Jonathan Escoffier's If I Survive You too, and in another year it might well have won this award. Your favourite literary character of 2023: Esme Nicoll in The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams. Unusually, my favourite character comes from my favourite novel of the year, but the character developmenbt was part of the reason why I so enjoyed Dictionary - I could have probably chosen a couple of others from the book as well. Your poetry recommendation of 2023: none Another award for which I read no books this year, again rather unusual. Your favourite genre of 2023: Historical fiction I could have just repeated last year's award, for African literature, and there were also 3 excellent Nordic novels I read this year, but I'm going for the broad category of historical fiction, which produced a string of cracking reads this year for me, including my top 2 novels, both added to my 'favourites' list. The funniest book you read in 2023: Standing Heavy by GauZ I generally don't find books funny, and this was certainly not a comedy! However, there were some wonderfully wry moments, with GauZ taking a very sceptical look at Western consumerism. Funny is probably the wrong word, but there was certainly some great humour there! Your favourite biography of 2023: Jeremy Hutchinson's Case Histories by Thomas Grant. I've not read many biographical books this year, but this isn't a 'default' winner, it is a genuinely great read, covering some of the most important legal cases of the 20th century. That sounds dry, but it's anything but. My only possible issue was that this did tend to the hagiographic, but one can understand why! Your non-fiction recommendation of 2023. Stolen Focus by Johann Hari. I've excluded books I've nominated for other non-fiction awards, not least because I've read a string of excellent non-fiction books this year, and want to spread the awards around a bit! This is probably the book I learned the most from (although it was pushed by Chris van Tulleken's Ultra-Processed People) - a fascinating, in-depth examination of the important issues surrounding the increasing problems of attention loss as a social problem. Actually, it partly led into the van Tulleken book. One I want to reread in 2024, there was so much to absorb. Your fiction book of the year, 2023: The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams Aside from the historical context, which already had me on side, I loved the character and plot development: these were people who I really cared about. I picked this up in my local bookshop on the spur of the moment, attracted by the theme(s) and knowing nothing else about it other than what I'd gleaned from a quick browse, and was wonderfully rewarded. It had to be good to beat my runner-up, the third volume in the excellent Chocolate House trilogy by David Fairer, Captain Hazard's Game. Both go on to my favourites list. Your author of the year, 2023. jointly James Baldwin and Annie Ernaux. Hmm, a tricky one as I've not read more than one book from any one author. But, whilst the books from these authors didn't (quite) make any of my other awards, they are perhaps the two authors I'm keenest to explore further. Your overall book of the year, 2023: October Sky by Hiram H Hickham Originally published as Rocket Boys, but renamed to tie in with the later film. A wonderfully engaging memoir of growing up and development beyond expectations in 1950s and 60s West Virginia, where coal is king, men are men, and small nerdy boys have a mountain to climb if they are going to make something of their lives. It has much to say about the world we live in today (good and bad), families, society and people in general. I was absolutely gripped from start to finish, and I'm not normally who is 'grabbled' by this type of book. My own categories, largely focused on non-fiction subjects I have a particular interest in: Favourite book in translation: Season of Migration to the North by Tayeb Salih A close run thing with Standing Heavy, and closely followed by a fistful of other books, but this was exceptional - not surprised it has been voted the most important Arab novel of the 20th century. A powerful post-colonial novel, where aspects of colonialism are completely inverted. Slim and very readable too! Favourite historical/geographical book: The Restless Republic by Anna Keay Excellent book on the brief period of republicanism in English history - filling in an almighty hole in my knowledge. Centred on and told through the lives of a handful of key characters, this was a fascinating read. Favourite environment/nature book: The Flow by Amy-Jane Beer Probably would have been non-fiction award winner if I hadn't had this specific category (and wanted to include Stolen Focus somewhere!). Beautifully written contemplation of our relationship with water, and rivers particularly, in the aftermath of the death of a close friend whilst kayaking. The fact that so much of it was based in landscapes with which I'm familiar made it all the more involving and personal, but the fact that it won the Wainwright Nature Writing award earlier in the year shows that this isn't necessary to appreciate this deeply thoughtful book.

-

Well, we've reached the end of the year, and as is traditional this thread is an opportunity for you to highlight your favourite reads of the year. Listed below are just the 'standard' awards, copied almost exactly from those posted by Ravenous in previous years (which I 'shamelessly copied' last year, and do again this year!). Please feel free to add any others that you want (I have a few of my own), and equally feel free to ignore any that aren't relevant to you So - Members of the Forum - without further ado, please tell us: Yes, I did buy it for the cover, but I stayed for the reading! Your favourite book cover of 2023. They print the words I like to read! Your favourite publisher of 2023. They sell me the words I like to read! Your favourite book shop/retailer of 2023. It was like when I was little, and Mummy used to read to me! Your audiobook recommendation of 2023. I even found one of their shopping lists! Your most read author of 2023. Stop me if you've heard this one before! Your recommended re-read of 2023. I'd rather be on I'm A Celebrity, Get Me Out Of Here! Your book that wasn't worth bothering with in 2023. I don't know where this year has gone! The book you most wanted to read in 2023, but didn't get too award. I'm sorry it wasn't a unicorn! Your biggest literary let-down of 2023. Think: Spot the Dog, BUT BETTER! Your favourite illustrated book of 2023. It's like living in Never-never Land! Your children's book recommendation of 2023. Most people pretend they have read this, but I actually did! Your recommended classic of 2023. Compact and bijou, Mostyn! Compact and bijou! Your favourite short story (or collection of short stories) of 2023. He made Mr Darcy look like Kermit the Frog! Your favourite literary character of 2023. Me talk pretty one day! Your poetry recommendation of 2023. I like things to be in boxes, nicely ordered boxes! Your favourite genre of 2023. I laughed so much, people moved away from me on the train! The funniest book you read in 203. After three years of COVID I have no life of my own anymore, so I just read about others! Your favourite biography/memoir of 2023. No, this really happened, yes it really did, I'm not making it up! Your non-fiction recommendation of 203.! Sounds like stuff someone made up! Your fiction book of the year, 2023. They've taken out a restraining order! Your author of the year, 2023. I'll read it again, I'll tell ya! Your overall book of the year, 2023. The small print (some repetition here!): Don't just make this a list, please explain your choices. Tell us what you really think about the books you have read. If there is a section you don't have a reply for, just skip it. Books don't have to have been published in 2023 to make it onto your list, you just have to have read them this year. Feel free to add your own categories, if you feel something has been missed.

-

The Years by Annie Ernaux ***** A memoir/autobiography quite unlike anything I've ever read before. Covering the whole of the post-war period, it may be autobiography, but it's all told in the third person, and is very much a life in the context of society as a whole covering key societal/political landmarks, if described from a personal perspective (on the left of the French political spectrum). The story is not just an account, but told through descriptions of photographs and other media, in relatively short and often apparently unrelated paragraphs. I was gripped by the writing, but have to admit that on several occasions when picking the book up again, I had to go back and reread the previous dozen or so pages: at the time of reading, everything felt very real and vivid, but so little actually stuck. I think this was primarily because so much of it was unfamiliar terrain - so many names that to a French man or women were probably commonplace, but to this British reader, completely unfamiliar (for instance, most French politicians other than the presidents!). Midway through, I started Googling unfamiliar names as they occured, and my retention levels did start to improve! As a result, I think that to fully appreciate this book, I will almost certainly have to reread it at some stage! In the meantime, it's an easy 5, and probably should be a 6 (if I can get to better grips with French cultural history!).

-

Your Book Activity 2023

willoyd replied to lunababymoonchild's topic in Book Blogs - Discuss your reading!

A few books read since the last post here, the latest, both this week, being Dictionary People by Sarah Ogilvie, and A Hero of Our Time by Mikhail Lermontov. Best of those not covered since my last post was definitely The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams, which is one of the very 6-star reads I've had this year. Not great literature, but a great story, really well meshed in with 'real' history. Loved it! More detailed comments on my blog thread. -

A Hero Of Our Time by Mikhail Lermontov *** Read for one of my reading groups. A short (barely 140 pages) novel set in the Caucasus of the early 19th century, featuring the somewhat amoral soldier Pechorin as the ironically titled 'hero'. This reads like a series of 5 short stories, told from different perspectives, examining Pechorin's sense of alienation from the society around him, and his refusal to conform: is he heartless or just brutally honest? I found this a difficult book to get into, really only grabbed by the fourth (and longest) of the five episodes - made all the more interesting (IMO) by the fact that it was told from Perchorin's perspective, thus seeing the world through his eyes rather than the rather mystified others around him. But maybe it was made more interesting by the fact that we'd seen him through the rather non-plussed eyes of other, more conventional, observers first? It'll be interesting to see what the rest of the group make of it. BTW, I looked forward to reading the introduction for insight, but found it hard going. One ot be read in small chunks, or, at least, not late at night!